He was a true artist on the base paths and a local pub recently honored him with a fitting tribute reflecting his tools of the trade.

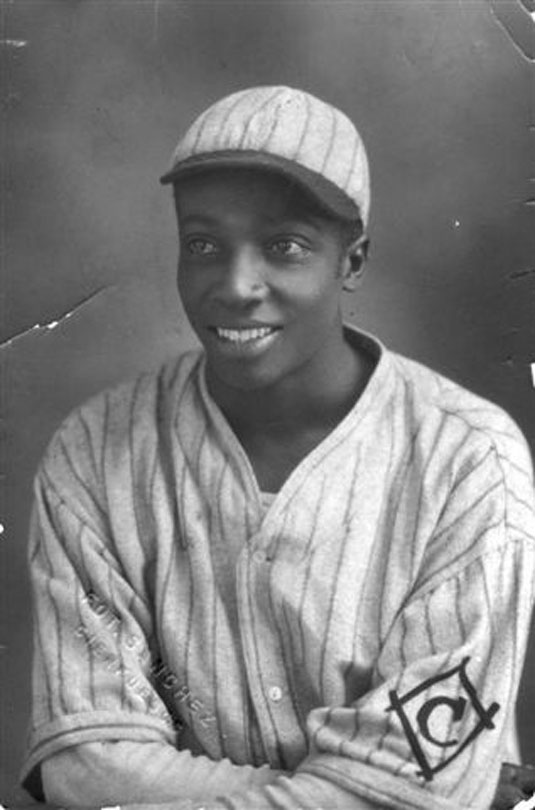

On September 21, the Royale on South Kingshighway hosted an art unveiling on their patio commemorating the baseball career of James Thomas “Cool Papa” Bell. A St. Louis-based art group called The Screwed Arts Collective were commissioned by the pub last spring to paint a piece paying homage to the legendary Negro Leagues baseball player, well-known for his tenure with the St. Louis Stars. The location of the exhibition seems fitting once you uncover the history attached to the bar’s association with baseball.

“There was a ballpark called National Night Field, South End Field, a few other names in varieties of that. It was a stadium that sat 6000 and had lights, which was unusual at the time in the late 1930, early 1940s,” Royale owner Steven Fitzpatrick Smith said to KMOX Sports leading up to the event. “Grover Cleveland Alexander played over there, Satchel Paige played over there, the Kansas City Monarchs had played over there. This is one of the places where you could truly see the best baseball being played, of all the real best players,” he said.

If the former ballpark next door was the place to observe the best baseball, then “Cool Papa” Bell was the feature presentation. Long before the days of Brock and Coleman, Bell was the preeminent base-burglar of his generation. His mythical speed and daring ability to circle the diamond made him one of the marquee athletes during the heyday of the Negro Leagues’ existence. Bell’s former roommate and power-hitting catcher Josh Gibson once remarked that Bell “was so fast he could flip the light switch and be in bed before the room got dark.” According to sports journalist Joe Posnanski, Olympic icon Jesse Owens used to thrill the crowds before Negro Leagues’ games by racing against the players. Owens rarely implemented his “no-racing clause” except only for one player: “Cool Papa” Bell.

The capability to score runs and disrupt the timing of the pitcher was the name of the game for Bell and his contemporaries. Bell not only utilized his running skill, but he incorporated a unique style of bunting, precise bat control, switch-hitting, and look to hit for contact to reach first base.

“We played a different kind of baseball than the white teams. We played tricky baseball. We did things they didn’t expect,” Bell said one time. “We’d bunt and run in the first inning. Then when they would come in for a bunt we’d hit away. We always crossed them up. We’d run the bases hard and make the fielders throw too quick and make wild throws. We’d fake a steal home and rattle the pitcher into a balk.”

His knack for stealing a base or two, however, wasn’t the inspiration behind one of the greatest nicknames in baseball history. Bell moved to St. Louis from Starkville, Miss. as a teenager and was highly-regarded early on for his prolific pitching prowess. Early-known recorded accounts courtesy of the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, NY indicates the former southpaw standout possessed a poised demeanor on the mound when hurling his patented pitches like his knuckleball, and thus the “Cool” moniker was born. The Hall of Fame credits his manager in St. Louis, Bill Gatewood, giving him the “Papa” part of his nickname because Gatewood stated it simply made it sound better.

An arm injury would eventually move Bell to center field where he went on to gain later notoriety as an innovator of the “small ball” strategy in baseball. The various testimonials from his teammates and rivals, though, are the only concrete evidence baseball fanatics have to revel in the career of Mr. Bell. There were little-to-no statistics documented during the glory days of the Negro Leagues due to minimal press coverage or the ones that were duly noted turned up lost and discarded forever. Bell wasn’t able to showcase his talent to Major League Baseball, as he retired in 1946, a year before Jackie Robinson made his debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Historians indicate by the few remaining recorded statistical evidence obtained over the years Bell was a lifetime .300 hitter with over 3,000 at-bats. He scored 717 runs, swiped 132 bags, walked 253 times, and notched 152 doubles and 51 triples. Despite the very little numerical proof, Bell was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1974, joining a class that featured the likes of Mickey Mantle, Whitey Ford, and another St. Louis baseball icon, “Sunny” Jim Bottomley.

To conclude this article, it’s truly fitting to showcase the legacy of one “Cool Papa” Bell. The everlasting praise he garnered during his playing career from his fellow immortals:

“Let me tell you about Cool Papa Bell. One time he hit a line drive right past my ear. I turned around and saw the ball hit his rear end as he slid into second. “- Satchel Paige.

“Next time up, he hit another one about the same place. Now nobody got a three-base hit in that little park, I don’t care where they hit the ball,” Yancey recalled, describing the Catholic Protectory Oval in the Bronx where he played with the New York Lincoln Giants. “And I watched this guy run. Well, he came across second base and it looked like his feet weren’t touching the ground! And he never argued, never said anything. That was why they called him Cool Papa; he was a real gentleman.” – Bill Yancey.

“Just how fast WAS Cool Papa Bell? Faster than that.” – Buck O’Neil.